By Grace de Rond | Dutch Version

By Grace de Rond | Dutch Version

"I had to walk barefoot through the snow for ten hours. Others had shoes, but not me, with my size 13 feet. I was feverish and exhausted, and I could hardly breathe because I had tuberculosis and pneumonia. When I fell for the third time, I couldn't get up. The soldier pointed his gun at me and shouted, "'Get up! I'd rather kill you than leave you here for the Allies to find!'"

Toine de Rond was 17 years old when Holland surrendered to the Nazis in May 1940. He had a nice girlfriend and a bright future as an artist. Eight months later, the Nazis began deporting Dutch citizens for forced labor - able-bodied men and women to work in its factories and sustain the war effort. The profile included healthy, non-Jewish males aged 18-50 and females 21-35.

From 1942, razzias were conducted, where thousands of Dutch citizens were gathered from public sites such as churches, markets, and street corners. Resisters were sentenced to penal work camps called strafarbeitslagers.

Between 1939 and 1945, the Nazis abducted more than ten million people from the defeated countries. According to the Red Cross, more than 500,000 of these were Dutch citizens. More than 30,000 of them died in camps.

It is mid-June, and Spring 2003 has been uncommonly beautiful in Holland, with record sunshine in March. Outside Toine's flat in a suburb of Rotterdam, it is still daylight at 9pm. In his darkish livingroom, Toine speaks reluctantly about what happened to him 60 years ago. He would rather talk about his favorite subjects: sports, or his son, Ron, and 13 year-old granddaughter, Zosha. Toine's only daughter, Marlo, died seven years ago of a brain hemorrhage.

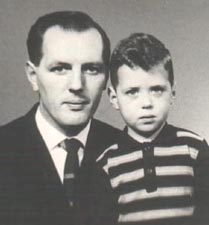

Toine is an attractive man, 6'2" and slender, with a firm handshake and an engaged look. His long graying hair is combed straight back from his high forehead. An early family photo of him at age 40 reveals the same soft mouth and intent eyes. Then and now, he expresses a wounded strength.

Though Toine speaks animatedly, his voice remains level, his tone pragmatic. He plants his feet on the floor, his elbows on his knees, and gestures continuously with his big hands, jabbing his fingers at the air like a professor waving not one, but two long pointers.

"At first, I was able to avoid the war. But in 1943, during the big razzias, the ground got too hot under my feet, so I escaped to Antwerp to live with relatives. When the war came close to Antwerp, I moved to another family in Paris. There I was fine for a while, until I learned that my mother had suffered a nervous breakdown. I decided to return to Holland. In November, when crossing the border from France to Belgium, I was captured for the first time."

During the fall of 1943, Toine was held in several prisons. He escaped from one, but an English-speaking person betrayed him by first gaining his trust and then returning him to the Nazis for a bounty.

"On December 3, 1943, I was transported to Siegen, Germany to work in a machine factory. The treatment was bearable, but we never heard anything from the outside world. Eventually, I found a way around that through a German family in Siegen. I could live there as long as I showed up for work every day. This family owned a radio, so I listened to Radio Oranje. And daily, I conveyed the news to my co-workers who were mostly French, Russian, Polish, and Dutch.

"Of course, not to the Germans!" he adds grinning

"Often, I had to tell the workers to be careful, because sometimes when the news was good they looked suspiciously happy. Everything went well, and optimism returned due to the good news on the radio. Although it was risky to listen to the news and spread the messages in the lion's den, I couldn't resist doing it because it was for a good cause."

When the Dutch government organized itself in exile in London, it sought a way to maintain contact with its citizens under occupation. The officials asked the British Broadcasting Corporation for transmitting time, and on July 28, 1940, Radio Oranje aired for the first time. Queen Wilhelmina spoke regularly to support the people back home. Jetty Pearl sang a popular cabaret song: "After rain always comes sunshine. After these dark days of high-handedness, disgrace, and terror, there will come a day of joy and reunion. We are proud and full of courage, because the people of Holland will persevere. The small country of Holland is fighting like a giant."

Radio Oranje was so popular with the Dutch people that the Nazis confiscated all their radios. Resisters were sentenced to the strafarbeitslagers.

"Unfortunately, just after the news of Normandy aired, my so-called freedom ended. I can still see myself running like a rabbit to my co-workers to tell them the great news of the Allied invasion. What a joy we felt!"

Toine's "so-called freedom" ended when several of his countrymen betrayed him. When confronted by guards, the Dutch workers responded that they had heard the news from "de Rond, who listens to the radio every day." At that point, Toine's circumstances worsened.

"What a terrible time, not knowing what would happen, just waiting for the verdict. I was kept in solitary confinement for three months. When I was finally taken to the court, the accusations against me were read aloud. Everything I said in my defense was ignored, while the 'witnesses' were believed. I still remember their names. Later, I learned that they had defected for money.

"The verdict was three years of hard labor in a strafarbeitslager - for listening to, and spreading info from, an 'enemy' radio broadcast."

Paintings hang in every room of Toine's flat, as well as in his ex-wife's flat where he still has dinner once a week, with her and her partner. Toine has painted all his life, mostly oil copies of masterpieces. His talent has been a god-send to a difficult life, especially since age forty-five, when he had his first heart attack and had to go on permanent disability.

Twilight is finally settling in, now that it is almost 10:30pm. Toine's shoulders droop only slightly as he rolls another cigarette and recalls his most difficult experiences. In October 1944, he was transported to the penal work camp at Frondenberg. He explains that after his trial, he was treated as an animal, what the Nazis called an Untermensch or subhuman.

"A lot of beatings, very little and poor food, inadequate clothes and shoes, and long, unbearable labor. I tried to escape, but I was caught and put in a special detention group where the guard was even more abusive. He would beat us with a bat, the butt of his rifle, or with stones. Whatever pleased the sadist. More than once he knocked me unconscious. There were sadists everywhere.

"I was put to slave labor in several prisons. I've done very hard labor in a stinking leather factory, a stone quarry in the mountains, a bomb shell factory, in steel mills where the ovens were too hot and still they made us keep working, carrying railroad ties to bombed railroad sites. Since I was the tallest in the group and therefore carrying most of the weight on my shoulders, I would sometimes collapse, but they would beat me until I got up again."

In his book, Inside the Vicious Heart, Robert H. Abzug describes a phenomenon called "double vision," which allows people to repress their emotions and become numb when faced with an individual's suffering through the hands of another. Allied soldiers experienced it when they liberated the camps in 1945 and could not comprehend what they saw. General George Patton purportedly ran behind a building to be sick. General Dwight Eisenhower radioed Washington that the "unspeakable conditions" were worse than anything yet reported.

The winter of 1944-45 was extremely severe for Holland. The Nazis blocked food shipments to the country, driving Dutch citizens to eat tulip bulbs to survive. People died of starvation in the streets.

As Allied troops grew closer in Spring 1945, Toine was moved from camp to camp. The Nazis raced to stay ahead of the approaching armies, forcing their emaciated and sick, often dying, prisoners on death marches.

"I spent March, 1945 at a camp in Munster. By then, I was very sick. 31 March was our last transport. We had to leave because the Allies were close. We had to march 14 hours to a prison in Klarholz. I was so sick that after 10 hours of walking I collapsed. I had fallen twice before, but with some severe beatings I was chased back to my feet. The third time, I couldn't get up because I couldn't breathe anymore."

The Nazis stuck sharp objects in the soles of the feet of men and women who had collapsed, to determine whether they were faking. Toine explains that as he lay in the snow for the third time, he resolved himself to remain still.

"The soldier in charge thought I was faking and was convinced that I wanted to stay behind to be rescued by the Allies. He pointed his gun at me and shouted, 'Get up!' What a terrible moment that was. I was sure I would die.

"This last transport would have meant the end for me if not for the Regierungsrat, the head of the camp who was walking with us. He saved my life when he said, 'Why don't you just toss him on the cart and we'll deal with him when we get to Klarholz.' "They did. And when we finally got to Klarholz, I escaped from the cart and hid in the barracks, behind the beds of the other prisoners. This is where I spent two days and nights."

Occasionally, as Toine tells his story, a roguish grin comes over his face. Then it is possible to still see the doggedness of a young man forced to mature quickly under impossible circumstances - yet still defiant, and eventually exhilarated, to win over an adversary too evil to comprehend. He grins in just such a way when he explains that he always referred to the Nazis as 'die herren,' the gentlemen.

"Die Herren didn't have much time for me anyway because the Allies were close, and they were too busy running in an effort to save themselves. At least that's what they thought!

"And then came 2 April. An unforgettable day!

"There he was, about 10:00am, an American officer, standing feet widespread, hands stuck casually in his pockets, a sten gun slung over his shoulder, on the threshold of our barracks. Now it was quickly over for the ones who ruled us. I can still see them trembling on their legs, 13 Nazi officers facing only one American! They were all arrested!

"On 9 April, we returned to our Fatherland where I was diagnosed with pneumonia and tuberculosis. My weight was 56 kilos where normally I was 85. Eventually, I had surgery on my lungs, and also on the injuries to my back from the beatings. On 22 June, I was finally brought home. My parents, my six older brothers, my sister - everyone was safe!"

After several operations and hospital stays, Toine spent five more years in sanatoriums - resting, retreating, and healing. But how does one heal from such an ordeal?

As Toine considers the question, he rises from his leather armchair to switch on several lamps, creating a glow that wards off the thick darkness outside. Gezellig is the word used by all Nederlanders to describe a warm, safe, lamp lit household. As he settles in his chair again, his words provide some clues to his recovery.

"It was a religious time. I'd been raised as a Catholic. Someone gave me a bidprentje [a small prayer-picture] of Beuron's Pieta. I loved that piece of work and decided to recreate it as a mosaic. It helped me pass the time."

Toine explains that he never actually finished the work, which stood in his basement for 50 years and now hangs in his son's home. The full work by Beuron is meticulously penciled to scale on the 2'x4' board, but only the two figures are completely filled in with tiny colored tiles. Toine's choice of theme is significant: the power of life over death, a wounded son in his mother's arms.

Perhaps life itself provides spurs to heal. In 1943, when the English-speaking person betrayed Toine, he swore he would never speak English again. He kept that promise for 50 years, until his son married an American woman. To communicate with her, he had to break his vow.

Two years ago, Toine ran into an old friend, the girlfriend from when he was seventeen. Today, as nighttime settles over Toine's rooms and paintings, they are once again sweethearts, and hopefully able to reclaim some of what was lost - still exhilarated to have won over evil in the end.

Grace de Rond

HOLLAND

gderond@cs.com